Achieving Robust Control with the Desired/Actual State Pattern

Spec and Status Patterns

- Achieving Robust Control with the Desired/Actual State Pattern

- Desired State Versus Actual State in Kubernetes

- Links

Achieving Robust Control with the Desired/Actual State Pattern

In the world of IoT and connected vehicle systems, the challenge of maintaining state consistency between a physical device and its digital counterpart is a critical design hurdle. Network latency, intermittent connectivity, and race conditions can create a frustrating and unreliable user experience. How can we ensure that a device's state in the cloud accurately reflects its real-world condition? The answer lies in a powerful design pattern: the separation of Desired State and Actual State.

This pattern moves beyond simple fire-and-forget commands to a more sophisticated model of state reconciliation, ensuring that systems remain synchronized and resilient, even in unpredictable network environments.

The Core Problem: State Discrepancy

Consider a simple smart home scenario: a user taps a button in a mobile app to turn on a light. The app sends a command to the cloud, which then relays it to the smart bulb. However, due to a spotty Wi-Fi connection, the command never reaches the bulb. The app shows the light as "On" (the intended state), but the bulb remains off (the actual state). This discrepancy leads to confusion and repeated, unnecessary user actions.

Now, apply this to a vehicle control system. A user sends a command to unlock the car doors. The system must not only send the command but also confirm that the doors have physically unlocked before updating the interface. A simple command-based approach is insufficient; the system requires a feedback loop to verify the outcome.

The Solution: Decoupling Desired and Actual States

The Desired/Actual State pattern addresses this by managing two distinct states for any given component:

Desired State: This represents the intended or requested state of the system. It's the "should-be" condition. For example, "the car doors should be locked," or "the air conditioner should be set to 22°C." When a user or system issues a command, it is the Desired State that is immediately updated.

Actual State: This is the real, verified state of the physical device, typically gathered from sensors or hardware feedback. It's the "as-is" condition, such as "the doors are currently locked," or "the air conditioner's sensor reports a temperature of 24°C."

The magic happens in the space between these two states. This is where the Reconciler and the Feedback Loop come into play.

Reconciler: This component, often implemented within a vehicle's Electronic Control Unit (ECU) or an IoT device's firmware, constantly compares the Desired State with the Actual State. If a discrepancy is detected, the Reconciler takes action to drive the physical component toward the Desired State. For instance, if the Desired State is "doors locked" but the Actual State is "doors unlocked," the Reconciler will trigger the door locking mechanism.

Feedback Loop: Once the Reconciler's action is complete and the hardware confirms the change, the Actual State is updated. This updated Actual State is then reported back to the server or application, closing the loop. This asynchronous callback mechanism confirms that the command was successfully executed and the physical state has changed.

Key Advantages of the Desired/Actual State Pattern

Adopting this architecture yields significant benefits for the robustness and scalability of connected systems.

- Clear and Asynchronous State Management: The pattern inherently accommodates the asynchronous nature of physical operations. A command to unlock a car door (updating the Desired State) is processed instantly from the user's perspective, while the system works in the background to achieve this state. The Actual State is only updated upon physical completion, providing a clear and accurate representation of reality at all times. The Desired/Actual State pattern typically requires a CALLBACK API on the caller's side, as it relies on asynchronous confirmation of the actual state. This makes it a natural fit for callback-based architectures, where updates and confirmations are event-driven rather than immediate.

- Enhanced Reliability and Safety: By continuously reconciling states, the system can automatically retry failed commands or alert the user if the Desired State cannot be achieved. In a vehicle, if a door fails to lock, the system can flag this inconsistency, preventing a potential security risk. This self-correcting behavior is fundamental to building dependable systems.

- Simplified Event-Driven Logic: This model makes it easy to trigger subsequent actions based on confirmed state changes. For example, you could design a sequence where the car's interior lights turn on only after the Actual State of the doors changes to "unlocked." This reliance on actual, confirmed states prevents logic errors that might occur if actions were triggered by a mere command.

- Scalability and Maintainability: The logic for controlling a component is neatly decoupled from its state representation. This makes it easy to apply the same pattern to new components—from windows and trunks to engine parameters—without rewriting the core control logic. This modularity is crucial for maintaining and scaling complex systems over time.

Conclusion

The Desired/Actual State pattern is more than just a technique for handling spotty connections; it's a fundamental architectural principle for building mature, reliable, and user-friendly IoT and connected vehicle systems. By shifting the paradigm from simple commands to state reconciliation, developers can create systems that are aware, resilient, and perfectly synchronized with the physical world they are designed to control. This approach ensures that what the user sees is what they actually get, building trust and delivering a truly seamless connected experience.

Desired State Versus Actual State in Kubernetes

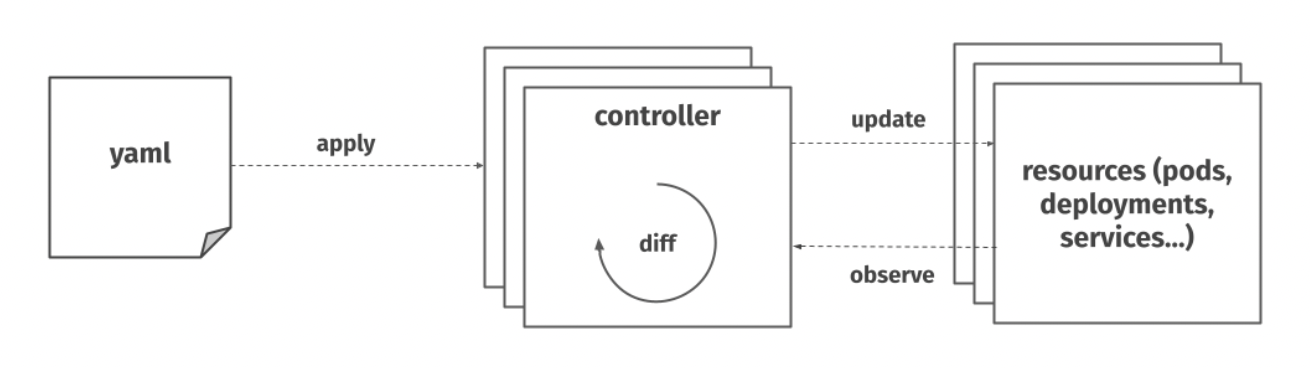

Desired/Actual State Patterns in Kubernetes:

- yaml: Desired State

- resources(pods, …): Actual State

By convention, the Kubernetes API makes a distinction between the specification of the desired state of an object (a nested object field called

spec(Desired State)) and the status of the object at the current time (a nested object field calledstatus(Actual State)). Over time the system will work to bring the status into line with the spec.

In distributed systems “Perceived State” refers to the imprecision of our measurements and lag time between when the system was measured and when we observe the results. In the HVAC example, you can think of the current temperature reported by the thermostat as being the Perceived State and know that the Actual State may have changed slightly since the temperature was last probed.

When you’re employing GitOps and IaC, your CD trigger is often the divergence between the actual and desired states.